In the previous installment of this series, we concluded

with a discussion of the madrigal and how it, in some ways, was the best

example of Renaissance style. The very end of the Renaissance, however, brought

about some very interesting developments. As history continued to march on,

with political, social and religious change, music was right there in the

middle of it. There were two topics I was hoping to cover today, but as I wrote

the body of the article, I realized that they are each so important to the

history and development of music as we know it, that they deserve their own

posts. Today, we’ll look at the music of the Reformation and

Counter-reformation, the influential composers of this phenomenon, and how sacred

music had to some extent come full circle. The second idea, which we’ll explore

in a couple weeks—is how secular composers followed the trends of the other

arts—visual and language arts—by showing extreme mannerism in their styles.

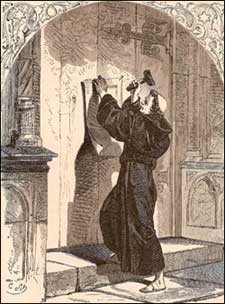

The Reformation, as nearly anybody would tell you, began in

1517 when Martin Luther nailed his ninety-five theses to the door of Wittenberg

Chapel in Germany. If I were to give you the whole backstory leading up to this

event, I’d need to start a whole new series. Suffice it to say that Luther and

several others began to realize that the one of the reasons the Catholic Church

held such a strong cultural hold on the people was the fact that few people any

more actually knew what was being taught. All the services—those beautiful

masses that we’ve discussed—were in Latin. Any sermons, any scriptures—all Latin.

With the spread of the Church across Europe, the large majority of the people

who worshiped in the church could not understand a word of what they were

told. And if you don’t understand it, you can’t refute it. This allowed

corruption and extortion to creep in, and the common parishioner was none the

wiser.

In order to combat this corruption, Luther broke away from

the Church, translated the scriptures and services into the vernacular, and

started teaching the average villager how to understand for himself. He did

write a German mass, but he also began to compose and teach simple chorales (a

vernacular version of the Latin motet). These were intended for congregation

singing, and home devotions, bringing sacred music out of the choir loft and to

the people. The texts and melodies were either adaptations of Latin chant, or

newly composed by Luther and others in the movement.

John Calvin and his reformation in Switzerland and France

produced a generous collection of accessible Psalm settings, and the English

quickly followed suit. They dropped the mass all together in favor of a simpler

service with anthems in English. There were elaborate versions for trained

choirs and special occasions, but the large bulk of the music was sung by the

congregation, and required little training. Because music was such a part of

devotion for these people, it was the religious reformers that did much of the

writing and composing of new pieces for worship. Many of these have become the

modern hymns of the Protestant Church.

The other half of this coin is the counter-reformation, or

the religious reformation accomplished from within the Catholic Church rather

than by breaking away from it. With so much upheaval, the Church leaders

realized that things weren’t running as they should, and that it was time to

re-evaluate. And here we come to the composer that many consider to be the

perfection of Renaissance counterpoint.

Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina was born in the 1520’s and

lived to the end of the century, working at St. Peter’s Basilica for much of

his life. He fine-tuned his counterpoint with such finesse that his sound is

like none other. Some of the qualities seen in his work include scoring for 4-6

voices but with each voice utilizing only a very tight-range, eliminating voice

crossing. His use of consonance and dissonance was very delicate, with enough dissonance

to create a satisfying resolution but keeping the imperfect consonances on the

strong beats. This practice went a long way in training the public to hear

pieces in either the major or minor keys, leaving behind some of the earlier

modes. His rhythm flows easily, not obscuring the text, but emphasizing it. One

other strong characteristic includes the elimination of parallel fifths and

octaves. Any theory student will have been beaten over the head with this rule,

but listening to the full, rich sound of Palestrina’s compositions proves the

point.

His most famous piece, the Pope Marcellus Mass, has because

the stuff of legend. It is said that during the Council of Trent—a meeting of

church leaders to discuss reforms—nearly banned polyphonic music from the

church, citing the focus on elaborate production rather than the text.

According to the story, it was Palestrina’s mass that convinced the council

that polyphonic music could be uplifting and sacred, not distracting. Listen to

it for a minute--or 30--and you’ll see why the Council was so affected by this piece

of genius.

He had contemporaries that pushed his rules somewhat. Tomas

Luis deVictoria is a Spanish composer who brought an exotic flair to sacred

composition without obscuring its use for worship. He was one of the first to

being using chromatics (sharps or flats not included in the key) as a way of

emphasizing words or intensifying cadences.

And so we see how sacred music began with very simple,

text-based compositions intended only to enhance the devotion of the participant.

Slowly, the various chants and services became more elaborate as artists

explored the possibilities of this new medium. In time, church authorities felt that the meaning of the text

was being lost, and the complex sacred motets of the early Renaissance

were becoming useless for worship. Now here at the end of the Renaissance, the

church—both Catholic and Protestant—has found a way to maintain the beauty and

complexity of its music without losing the original purpose.

Next post, we'll look at the craziness that was the end of the Renaissance in the world of secular music, and how it paved the way for the Baroque era of Monteverdi, Corelli, Handel and Bach.

Well, you know, complicated music and unintelligible words aren't necessarily useless for worship. That is really a matter of opinion. (And it ain't my opinion!)

ReplyDeleteVery good point! I should have made it clearer that I was simply stating the historical viewpoints of those responsible for making decisions on music in the church (i.e. the Council of Trent or Martin Luther). Actually, I think I'm going to edit the article appropriately. Thanks for the comment! What do you think of the rest of the series?

Delete